Product

Split Core Current Transformers

Current sensors serve as the “senses,” responsible for detecting current signals; current transmitters, however, go a step further. They not only detect but also ‘translate’ the detected signals into a universal, standardized “language” that other devices can understand and utilize.

| Current Sensor | Current Transmitter |

| Signal | Output the raw or primary processed signal. The output signals can take various forms—they may be weak voltages or currents proportional to the measured current, or even digital signals. For example, a Hall‑effect sensor outputs a millivolt‑level voltage signal, while a current transformer (a basic type of current sensor) outputs a small current proportional to the turns ratio (such as 0–5 A). These signals are generally not universal and require further processing by subsequent circuits. | Output standardized industrial signals. Its core function is to convert and amplify the signals detected by the sensor into standardized analog signals commonly used in industrial control systems—most typically a 4–20 mA DC current signal, or a 0–10 V / 0–5 V DC voltage signal. These standardized signals can be directly recognized by devices such as PLCs, DCS systems, and data acquisition cards. |

| Transmission | Short transmission distance, susceptible to interference Prone to electromagnetic interference, cable length, and resistance, leading to signal distortion or errors. Therefore, sensors typically need to be installed close to the signal processing unit. | Long transmission distance and strong anti‑interference capability. The 4–20 mA current‑loop signal offers excellent resistance to interference. In a current loop, as long as the current remains constant, variations in line resistance do not affect signal accuracy. This makes it highly suitable for reliable long‑distance transmission—up to several hundred meters—from field devices to a central control room. |

| Application | As a core sensing component, it is widely used. It forms the foundation of all current‑measurement applications and is integrated into a wide range of devices. For example: Consumer electronics: Used in smartphone chargers for fast‑charging control. New energy vehicles: Monitors charging and discharging in the Battery Management System (BMS). Inverters / converters: Used for motor control and Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT). | Primarily used in industrial automation and process control systems. When the operating current of field equipment—such as motors or heaters—needs to be used as a parameter and transmitted to a remote PLC or SCADA monitoring system, a transmitter becomes essential. Its role is to serve as a signal bridge between field devices and the control system. |

| Difficulty | More complex to use and requires secondary development. Users must design their own peripheral circuits—such as amplification, filtering, and linear‑compensation circuits—to process the sensor’s raw signal before it can be converted into meaningful data or used for control. This places certain requirements on the user’s circuit‑design capabilities. | Easy to use and plug‑and‑play. The transmitter integrates all necessary signal‑processing circuits internally. Users only need to follow the wiring instructions (power supply, input, and output) to connect it directly to the analog input ports of standard instruments or controllers, without requiring complex circuit design. |

Core Summary

Relationship: A current transmitter can be regarded as an upgraded or integrated version of a current sensor. It contains a built‑in current‑sensing element and adds signal‑conditioning and standardized‑output circuitry.

Key Difference: The essential distinction lies in the nature of the output signal. A sensor outputs the raw material—a primitive, unprocessed signal. A transmitter outputs a standardized, ready‑to‑use signal.

How to Choose:

- If your design is on a PCB and requires precise current measurement and control—such as inside a power supply or motor driver—you would choose a current sensor chip or module.

- If you are in an industrial environment and need to monitor the operating current of a large water pump located tens of meters away, and send that data to a central control room for display and logging, you must use a current transmitter.

The Rogowski coil is a hollow ring-shaped coil arranged around a conductor. Its operating principle is based on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction: the alternating magnetic field generated by current induces a voltage in the coil that is proportional to the rate of change of current (di/dt).

Therefore, traditional Rogowski coils cannot measure static direct current.

However, they can measure the rapidly changing portion of pulsed DC signals, significant DC offsets, or the AC components of DC signals.

Without an integrator, the signal obtained is di/dt rather than the current itself.

This means:

- 1. Time-domain measurements (waveforms, RMS, energy) will be completely distorted

- 2. It can only be used for frequency-domain analysis (e.g., harmonics, high-frequency transients)

- 3. It cannot be used for conventional applications like energy metering, protection, or monitoring

In other words, without an integrator, a Rogowski coil cannot function as a standard current sensor.

While an integrator is almost always essential, exceptions exist:

- 1. Devices with built-in integrators

Many modern power measurement chips (ADE7953, ATM90E32AS), energy meters (iEM3555, MD-P1-3-RC-16), and power analyzers (ABB M4M, PW3390), and DSP processors with integrated digital integrators (ADS131E08, TMS320F280049, MCP3910, STM32G4).

- 2. Specialized applications

Certain motor fault detection or pulse current testing applications focus solely on high-frequency di/dt and can utilize the raw signal directly.

- 3. “Self-Integration” Scenarios

When the pulse width is significantly shorter than the coil’s time constant, the coil itself exhibits approximate integration characteristics. However, this represents a very niche application.

Current transformer, abbreviated as (CT), is a device used for measuring alternating current. It converts large current into a smaller current through the principle of electromagnetic induction, making it convenient for measurement, protection and control. Low-voltage current transformers and high-voltage current transformers are mainly distinguished based on their working voltage levels. Low-voltage current transformers are typically used in power systems with an alternating voltage of 1000V (1kV) or below. High-voltage current transformers are used in ultra-high voltage power grids ranging from 1kV to 100kV.

Main differences comparison

| Low Voltage CT | High Voltage CT |

| Voltage Level | It is typically applicable to low-voltage systems of 1kV and below (such as 0.4kV, 0.66kV). | It is suitable for high voltage systems above 1kV (such as 10kV, 35kV, 110kV or even higher). |

| Insulation level | The insulation requirements are relatively low, and dry insulation (such as epoxy resin casting or air insulation) is often used, with a low withstand voltage. | High insulation requirements are required, and oil-immersed, SF6 gas insulation, or composite insulation are often used to withstand high voltage and prevent breakdown. |

| Structural design | It has a simple structure, small size, and light weight, and is usually a ring or rectangular iron core, making it easy to install. | The structure is complex and the volume is large, which may include porcelain sleeves, oil tanks or gas chambers to ensure safe isolation. |

| Application | It is widely used in low-voltage distribution cabinets, industrial control systems, metering instruments, and household appliance protection. | It is widely used in high-voltage substations, transmission lines, and power plants for measurement, protection relays, and fault monitoring. |

| Safety and Maintenance | It is easy to install and maintain, has low cost, and low risk. | It has strict safety requirements, is complex to maintain, requires regular inspection of insulating oil or gas, and is costly. |

| Standards and Specifications | It complies with standards such as IEC 61869-2, but focuses on low-voltage safety. | It complies with standards such as IEC 61869-2, emphasizing high-voltage insulation and shock resistance. |

The current transformer ratio represents the ratio of primary to secondary current, for example, 500/5, 250/5, or 100/5. A ratio of 500/5 indicates that when the primary current reaches 500A, the secondary current is 5A.

Standard primary-side rated current ratios include 20, 30, 40, 50, 75, 100, 150, and 2×a/C, with secondary-side rated currents typically being 1A or 5A. The notation 2×a/C signifies a dual-ratio transformer achievable through series (a/c) or parallel (2×a/C) connection of internal components. For metering applications, the primary rated current (I1n) should be greater than or equal to the calculated load current (IC). For instance, a load current of 350A would require a 400/5 current transformer. For protection applications, a larger transformation ratio may be selected to ensure accuracy.

Rogowski coils, also known as hollow coils or flexible current transformers, have gained widespread application in power monitoring, high-frequency pulse current measurement, and high-current protection due to their significant advantages such as non-magnetic saturation, wide measurement range, and easy installation. However, in practical applications, Rogowski coils cannot typically be directly connected to measuring instruments but must be used in conjunction with an integrator.

1. The Physical Nature of the Rogowski Coil: di/dt Sensor

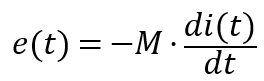

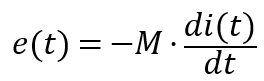

The operating principle of the Rogowski coil is based on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction. When the measured current i(t) passes through the center of the coil, an induced electromotive force e(t) is generated within the coil. Its mathematical expression is:

Here, M represents the mutual inductance coefficient between the coil and the primary conductor.

From the formula, it can be seen that the output voltage of the Rogowski coil does not directly correspond to the magnitude of the current, but is proportional to the rate of change (derivative) of the current. This means:

• If the current is a constant direct current, the output of the Rogowski coil is zero.

• If the current is a sine wave, the output voltage will lead the current by 90° in phase, and its amplitude will increase linearly with frequency.

Therefore, to reconstruct the true current waveform i(t), the output signal from the coil must undergo mathematical integration processing.

2. Core Functionality of the Integrator

The integrator plays a crucial role in the Rogowski coil measurement system, with its functions primarily manifested in the following three aspects:

1 Waveform Reconstruction (Integration): An electronic integration circuit (typically an active integrator composed of operational amplifiers) converts the di/dt signal into a voltage signal proportional to i(t).

2 Phase Correction: Compensates for the 90° phase lead generated by the Rogowski coil, ensuring the output signal is in phase with the original current signal. This is critical for power measurements, such as calculating power factor.

3 Signal Conditioning and Amplification: The raw induced voltage from the current loop is typically very weak (millivolt level). The integrator amplifies it to standard levels and enhances drive capability for long-distance transmission or load driving.

3. Comparative Analysis of Common Output Types for Integrators

Depending on the specific requirements of the backend receiving equipment (such as electricity meters, PLCs, oscilloscopes, or relay protection devices), integrators are designed with multiple output formats. The following table provides a detailed comparison of these common output types:

| Output Type | Typical Specifications | Signal Characteristics | Primary Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Instantaneous voltage output | 333mV AC, 1V AC | AC Waveform | Digital Energy Meters, Power Analyzers | High safety (no secondary open-circuit high voltage), excellent linearity | Limited transmission distance, susceptible to electromagnetic interference |

| Instantaneous current output | 1A AC, 5A AC | AC Waveform | Replacing traditional current transformers (CTs), relay protection | Compatible with legacy equipment, strong drive capability, suitable for remote transmission | High power consumption, requiring high-power power supply support |

| Standard analog signal | 4-20mA DC, 0-1V DC | DC/Process Signal | PLCs, DCS, industrial automation control systems | Strong anti-interference capability (4-20mA), easy system integration | Loss of original waveform information, reflecting only the effective value |

| Output without integrator | Voltage(di/dt) | AC Differential Waveform | High-frequency transient analysis, data acquisition devices with built-in integration capabilities | Extremely high bandwidth, no integral drift, fastest response | Cannot directly read current values, requiring complex backend processing |

This is currently the most prevalent output method for Rogowski coils. 333mV represents the standard low-voltage transformer specification widely adopted in North America and internationally. The primary advantage of this output method is safety: even if the secondary circuit is disconnected, it does not generate lethal high voltages like traditional current transformers. It perfectly preserves current harmonic information, making it ideal for high-precision power quality analysis.

To maintain compatibility with secondary instruments originally designed for traditional core-type CTs, integrators can output 1A or 5A currents. This type of integrator essentially functions as a “voltage-to-current” power amplifier. It resolves the issue of Rogowski coils being unable to directly drive high-impedance loads. However, due to the need to output larger currents, the integrator’s own power consumption and physical size increase significantly.

In industrial automation, users often require only the RMS value of current without needing to inspect waveforms. These integrators incorporate internal RMS-DC conversion circuits that transform complex AC signals into stable DC signals. The 4-20mA current loop output offers exceptional noise immunity, making it ideal for long-distance transmission to PLC or DCS systems.

In specialized scientific applications, such as lightning current measurement or high-energy physics experiments, users may directly capture the raw di/dt signal from the Rogowski coil. This approach bypasses bandwidth limitations and low-frequency drift inherent to integrators, enabling digital integration via post-processing algorithms to achieve extremely high measurement bandwidths (up to several MHz or higher).

4. Summary

The integrator addresses core issues of waveform reconstruction, phase correction, and signal amplification.

Selecting the appropriate output type depends on your backend equipment:

•For precision and safety, choose 333mV/1V AC;

•For compatibility with legacy systems, choose 1A/5A AC;

• For industrial monitoring, choose 4-20mA DC;

•When using metering equipment compatible with Rogowski coils or conducting high-frequency research, consider utilizing the direct di/dt output.

By properly matching the Rogowski coil with the integrator, you can fully leverage its non-saturating, wide-range capabilities to achieve precise control over complex current environments.

In power systems, precise energy metering is the cornerstone for fair transactions, energy conservation, and stable system operation.

As a critical component in energy monitoring systems, the accuracy of current transformers (CTs) directly determines the precision of final readings.

However, beyond the well-known “ratio error” (amplitude error), a frequently overlooked yet crucial parameter—phase angle error—can have a critical impact on energy measurement accuracy under specific conditions.

To understand phase angle error, we must first recognize the gap between ideal theory and practical reality.

- Ideal scenario: An ideal current transformer should output a secondary current signal that is exactly opposite in phase to the primary (main circuit) current signal, maintaining a perfect 180° phase difference.

- Reality: In actual transformers, the secondary current phase does not precisely oppose the primary current by 180°, but instead exhibits a slight angular deviation. The angle between this actual secondary current vector and the ideal opposing primary current vector is defined as the phase angle error.

According to international standards, when the secondary current vector leads the ideal position in phase, the phase angle error is positive (+); conversely, when it lags, the phase angle error is negative (-).

This seemingly insignificant angle is crucial for high-precision energy metering.

The root cause of phase angle error lies in the inherent characteristics of the transformer’s physical structure and electromagnetic principles, specifically the presence of the excitation current.

Current transformers operate similarly to transformers: primary current flowing through the core generates a magnetic field, which in turn induces a secondary current.

To establish this necessary magnetic field in the core, the transformer itself consumes a portion of energy. The current corresponding to this energy consumption is the exciting current.

- Magnetizing Component: Used to establish the magnetic field in the core, its phase lags behind the induced electromotive force by 90°.

- Iron loss component: Compensates for energy losses in the core due to hysteresis and eddy currents under alternating magnetic fields. Its phase is in phase with the induced electromotive force.

Since the primary current I₁ equals the vector sum of the secondary current I₂ (converted to the primary side) and the excitation current I₀ (I₁ = I₂ + I₀),

the presence of the non-coincident excitation current I₀ inevitably creates a phase difference between I₁ and I₂.

This phase difference ultimately manifests as the angle difference in the mutual inductor.

Simply put, the angular difference is essentially a “disturbance” in the phase relationship of currents caused by the excitation current.

All factors affecting the magnitude and phase of the excitation current—such as the magnetic properties of the core material, the load (burden) connected to the secondary side, and the magnitude of the primary current itself—directly influence the angular difference.

3. How Does the Angular Difference Affect the Accuracy of Electrical Energy Monitoring?

The formula for calculating electrical energy (active power) is:

P = U × I × cos(φ), where φ is the phase angle between voltage and current, and cos(φ) represents the power factor.

Phase angle error in the transformer directly alters the phase angle φ measured by the energy meter, leading to errors in power calculation.

Error propagation relationship: The total error in energy measurement is approximately equal to the sum of the voltage ratio error, current ratio error, and phase angle error.

A simplified formula can be expressed as:

Power measurement error ≈ Voltage ratio error + Current ratio error + tan(φ) × Δφ

Where Δφ represents the phase angle error introduced by the instrument transformers.

Key Influencing Factor: Power Factor

- High power factor (cos(φ) ≈ 1, φ ≈ 0°): tan(φ) is very small, and the angular error Δφ contributes minimally to the total error. Measurement error is primarily determined by the “ratio error” (amplitude error).

- Low power factor (cos(φ) → 0, φ → ±90°): tan(φ) becomes extremely large. Even a small phase angle error Δφ, amplified by tan(φ), can cause significant power measurement errors.

For example: In a circuit with an extremely low power factor, even if the ratio error (amplitude error) of the instrument transformer is very small,

the final calculated energy reading may still deviate significantly from the true value if any phase angle error exists.

4. Manifestations of Phase Angle Error Impact

- Inductive loads (e.g., motors, transformers with lagging power factor): A positive phase error typically causes the meter reading to exceed actual energy consumption, resulting in unnecessary electricity charges for the user.

- Capacitive loads (e.g., capacitor banks, excessively long cables, leading power factor): A positive phase angle error causes the meter reading to understate actual energy consumption, resulting in losses for the power supplier.

In modern industrial and commercial settings, the widespread use of variable frequency drives, motors, LED lighting, and switching power supplies has made grid power factor increasingly complex and often suboptimal.

Against this backdrop, the phase angle difference of current transformers has evolved from a secondary parameter into a critical factor determining whether an energy monitoring system can operate with “accuracy and fairness.”

Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) is a critical design consideration in modern electronic equipment. Electromagnetic interference (EMI) not only affects the normal operation of equipment, but can also violate regulatory requirements. To effectively suppress these disturbances, engineers use a wide range of filtering components, with inductors playing a central role. Among the many types of inductors, Common Mode Chokes and Differential Mode Inductors are two of the most commonly used and have very different functions.

Although both are used for EMI filtering, the types of disturbances they target, their structures and operating principles are very different. In this article, we will discuss the essential differences between common mode choke and differential mode inductors, their application scenarios, and provide practical selection points to help engineers make the right choice in circuit design.

1.1 Definition and Operating Principle

A common mode inductor, also known as a common mode choke, is a filtering element primarily used to suppress common mode interference.

Common Mode Noise (CMN) is a noise signal with the same direction and size on two signal lines (e.g., power lines L and N, or data lines D+ and D-) relative to the ground or reference plane. This interference is usually caused by external EMF coupling or unbalanced circuitry within the device and is radiated outward through the cable or introduced into the device internally through the cable.

The typical construction of a common mode inductor is that two or more sets of coils are wound on the same high permeability ferrite core with the same number of turns and orientation.

The operating principle is based on magnetic field cancellation and high impedance effects:

For differential mode signals (useful signals): When normal differential mode currents (i.e., signals of opposite directions and equal sizes on two lines) flow through two windings, the magnetic fluxes they generate in the cores are in opposite directions and cancel each other out. Therefore, the impedance of a common mode inductor to a differential mode signal is extremely low and hardly affects the transmission of useful signals.

For common-mode signals (noise): When common-mode currents (in the same direction) flow through two windings, they generate magnetic flux in the core in the same direction, superimposed on each other. This causes the core to exhibit high inductance, which creates an extremely high impedance to common-mode noise and achieves the purpose of suppressing and attenuating common-mode interference.

1.2 Structural Characteristics

Common mode choke usually have four pins (two inlets and two outlets) and are composed of two windings with the homonymous ends of the windings located on the same side of the magnetic ring.

Differential Mode Inductor

2.1 Definition and Working Principle

Differential Mode Inductor is a traditional inductive component mainly used to suppress differential mode interference.

Differential Mode Noise (DMN) is a noise signal with opposite direction and unequal size between two signal lines. This kind of interference is directly superimposed on the useful signal and is usually caused by internal factors such as the switching action of the switching power supply, load changes or signal line impedance mismatch.

The structure of a differential mode inductor is similar to that of an ordinary inductor, which usually has only one winding, wound on a magnetic core.

Its working principle is based on the self-inductive effect of the inductor:

For differential mode signals (useful signals and noise): A differential mode inductor impedes the change of current flowing through itself. Whether it is a normal differential mode signal or differential mode noise, as long as the current flows through the inductor, it will be affected by its inductance.

Filtering effect: differential mode inductor through its high frequency impedance characteristics, the high frequency of the differential mode noise attenuation, while the low frequency of the useful signals (such as power supply DC or low-frequency AC component) to maintain a low impedance, so as to achieve filtering.

2.2 Structural Characteristics

Differential mode inductors usually have only two pins and only one winding. In EMI filtering circuits, it is usually connected in series on the power or signal line.

Core Differences Comparison

The core distinction between common-mode chokes and differential-mode chokes lies in the types of noise they address, their structural design, and their impact on useful signals. The table below summarizes the key differences between the two:

| Characteristics | Common Mode Choke | Differential Mode Inductor |

| Suppression target | Common-mode interference (noise in the same direction relative to ground) | Common-mode interference (noise between signal lines) |

| Working Principle | Flux superposition produces high impedance (for common mode), while flux cancellation produces low impedance (for differential mode). | Self-inductance creates high impedance (to all high-frequency currents) |

| Structure | Two windings, wound in the same direction on the same magnetic core | A winding, wound around the magnetic core |

| Number of pins | 4 (two in, two out) | 2 (one in, one out) |

| For useful signals | Extremely low impedance with virtually no attenuation | There is a certain amount of impedance, which may cause slight attenuation of the useful signal. |

| Application Location | Typically used at the input/output ends of power cables or high-speed signal lines to filter out radiated interference. | Typically used in series with power cables or signal lines to filter out conducted interference. |

Application Scenarios

4.1 Application Scenarios for Common-Mode Chokes

Due to their excellent suppression of common-mode noise without affecting differential-mode signal transmission, common-mode chokes are widely used in the following scenarios:

- Switching Power Supplies (SMPS): At the input stage of AC/DC or DC/DC converters, they suppress common-mode noise generated by switching operations, preventing its conduction and radiation through power lines.

- Data Communication Interfaces: High-speed differential signal lines such as USB, HDMI, and Ethernet (RJ45 connectors). Common-mode chokes effectively filter externally coupled common-mode noise while preserving differential signal integrity.

- Automotive Electronics: Employed in vehicle networks (e.g., CAN, LIN) and power lines to withstand complex electromagnetic environments.

4.2 Differential Mode Choke Applications

Differential mode chokes primarily suppress differential mode noise on power lines, often paired with capacitors to form π-type or L-type filters:

- Power Line Filtering: At power inputs, combined with X capacitors to create differential mode filter circuits that attenuate internally generated differential mode conducted interference.

- Low-frequency applications: Suitable for low-frequency power filtering or signal processing circuits where high-frequency signal attenuation is not critical.

- DC/DC converter outputs: Used to smooth output current and suppress the differential mode component in switching ripple.

Selection Criteria

Proper selection is critical to ensuring effective EMI filtering. When choosing common-mode and differential-mode inductors, the following core parameters must be considered:

Rated Current (I_rated): The choke must withstand the circuit’s maximum continuous operating current.

Common Mode Impedance (Z_CM): This is the most critical parameter. Select chokes exhibiting maximum impedance at the target noise frequency (typically tens to hundreds of MHz). Higher impedance yields better suppression.

Differential Mode Impedance (Z_DM): Select inductors with low differential mode impedance to minimize attenuation of useful signals.

DC Resistance (DCR): Lower DCR is preferable to reduce power loss and temperature rise.

Operating Frequency Range: Select appropriate core material and winding structure based on the circuit’s operating frequency and noise frequency.

5.2 Key Considerations for Differential Mode Inductor Selection

Inductance (L): Determine the inductance value based on the required cutoff frequency and filtering characteristics. Higher inductance provides better attenuation of low-frequency noise.

Rated Current (I_rated): Similar to common-mode inductors, it must meet the circuit’s maximum operating current requirement.

Saturation Current (I_sat): When current increases beyond a certain threshold, the core saturates, causing inductance to drop sharply. During selection, the saturation current must exceed the peak current in the circuit to ensure filtering performance.

DC Resistance (DCR): Similarly, DCR should be as low as possible.

Conclusion

Common-mode ckoke and differential-mode inductors are the two indispensable forces in EMI filter circuits. Common-mode inductors, with their unique dual-winding structure, efficiently suppress common-mode interference while protecting the integrity of useful signals. They are the preferred choice for high-speed signal and power line radiation suppression. The differential mode inductor, through the self-inductance effect, directly attenuates the differential mode interference and is the cornerstone of power conduction filtering.

Understanding the fundamental differences among them: different suppression objects, different structures, and different working principles, is the basis for correct circuit design and component selection. Only by reasonably combining the specific types of interference and circuit requirements can an electronic system that meets strict EMC standards be constructed.

In power systems, measuring devices such as electricity meters typically need to be connected to high-voltage or high-current circuits via current transformers (CTs). A common standard is that the interface parameters of electricity meters and the rated secondary current of their matching CTs are almost always 5A (or 1A). This article will delve into the reasons behind this standard and, in conjunction with common parameter markings on electricity meters, explain how to correctly select the matching current transformer.

The current transformer parameters supported by the meter are usually marked on the meter, such as 0.25-5(6)A, 0.015-1.5(6)A, 0.25-5(80)A, 0.25-5(100)A, etc. These parameters identify the operating range and technical requirements when connecting to an external CT. These parameters identify the operating range and technical requirements of the meter when connected to an external CT:

Take 0.015-1.5(6)A as an example:

* Starting current (0.015): the minimum current of 15mA that the meter can accurately measure.

* Basic current Ib(1.5):The rated current value of the energy meter is 1.5A, and the accuracy level of the energy meter can be guaranteed when it works under this current.

* Maximum current Imax(6): the maximum current at which the meter can be carried safely and continuously without damage, 6 A. This is covered in the IEC/EN 62053 specification for electricity meters.

2. How to select the correct current transformer (CT) according to the parameters

Two core principles must be followed in selecting a matching current transformer: secondary current matching and primary current sizing.

a. Matching of rated secondary current (key)

The rated secondary current of the CT must match the basic current Ib of the energy meter.

– For meters with parameters 0.25-5(6)A, 0.25-5(80)A, 0.25-5(100)A, you need a current transformer with a 5A rated secondary current.

– For energy meters with parameters 0.015-1.5(6)A (used in specific scenarios although the base current is not 5A/1A standard), you need to equip a CT with a rated secondary current of 1.5A (these are less common and usually follow the 5A or 1A standard).

b. Selection of Rated Primary Current and Variable Ratio

The rated primary current of the CT (which determines the variable ratio, e.g., 100/5A, 500/5A, 100/1A) should be selected in accordance with the load current of the actual primary circuit. The selection principle is to make the actual load current of normal operation close to the rated primary current of the CT. According to IEC/EN 61869 standard, 1.2 times of the rated primary current is also in line with the nominal accuracy of the product, so the best measurement accuracy can be ensured.

Therefore, for energy meters with parameters of 0.015-1.5(6)A, the best match is a current transformer (CT) with a secondary rated output of 1A.

If you are interested in the measurement of small currents and do not have high requirements for measurement accuracy and range, you can also choose a current transformer (CT) with a secondary rated output of 100mA.

3. Why has 5A (or 1A) become the industry standard?

Returning to the question at the heart of the article, why has the industry generally adopted 5A or 1A as the standard secondary current for CTs? The reason is a combination of performance, standardization, and safety:

Performance Requirements and Historical Reasons

Early electromechanical energy meters and protective relays required a certain amount of physical energy (power) to actuate the mechanical components. 5A current provided a strong enough signal and power to ensure reliable and accurate operation of these devices. Current signals in the milliamp range are too weak, susceptible to interference and unable to drive older devices.

Standardization and Global Interchangeability

5A is established as the global standard for the power industry, ensuring that devices from different manufacturers and countries are easily compatible and interchangeable, greatly simplifying system design, manufacturing and maintenance.

Balancing Safety and Economy

The core safety objective of the CT is to isolate the high voltage high current circuits from the low voltage measurement circuits. 5A’s relatively low secondary current reduces operational risk. At the same time, the 5A strikes a good balance between cabling costs, wire cross-section requirements and power loss. Where long wiring distances are required, the 1A standard is used to further reduce line losses (1A losses are only 4% of 5A).

In summary, the selection of 5A (or 1A) as the standard secondary current for CTs is the result of engineering practices that optimize performance, cost, historical compatibility and operational reliability.

The Rogowski Coils (RC) and Current Transformers (CTs) are two core technologies for measuring alternating current, both of which operate based on the principle of electromagnetic induction. However, there are fundamental structural differences between the two the design with or without a magnetic core leads to significant differences in their performance, application scenarios and safety. CT adopts a core structure and performs exceptionally well in high-precision, low-frequency and steady-state measurements. RC adopts a coreless design, featuring greater flexibility, a wider dynamic range and anti-saturation characteristics, making it an ideal choice for high-current, high-frequency and transient applications.

I. Fundamental Differences: Principle and Structure

The core design is the most critical differentiator between the two technologies.

| Feature | Rogowski Coil (RC) | Current Transformer (CT) |

| Core Structure | Coreless (Air-core). | Iron Core (Heavy magnetic core). |

| Working Principle | Based on Faraday’s Law of Induction. Generates a voltage proportional to the rate of change of the primary current (di/dt) . | Based on electromagnetic induction. Relies on magnetic coupling via the core to transform primary current to secondary current. |

| Output Signal | Low-level voltage signal(di/dt). | Current signal (typically 5A or 1A secondary). |

| Signal Processing | Requires an external integrator circuit to convert the derivative voltage signal back into a signal proportional to the current. | Output current is typically measured directly or converted to voltage via a burden resistor. |

II. Performance and Safety Comparison

The coreless design of the Rogowski coil provides distinct advantages in dynamic range and safety, while the iron core of the CT offers inherent simplicity and high accuracy at rated conditions.

| Characteristic | Rogowski Coil (RC) | Current Transformer (CT) |

| Core Saturation | None. Immune to magnetic saturation, even at extremely high currents. | Prone to saturation when exposed to currents higher than its rating, leading to non-linear response and measurement failure. |

| Measurement Range | Very Wide. Can measure from a few Amps up to thousands of Amps (e.g., 10kA) with a single unit. | Narrower. Limited by the core size and saturation point. Different CTs are required for different current ranges. |

| Frequency Response | Superior/Wide Bandwidth. Excellent response for high-frequency and transient currents (e.g., motor inrush, pulsed currents). | Limited. Frequency response is restricted by the core material. Best suited for power-line frequencies (50/60 Hz). |

| Linearity | Excellent. Maintains linear response over its entire wide measurement range. | High Accuracy at rated current and frequency, but linearity degrades significantly upon saturation. |

| Safety (Open Circuit) | Inherently Safe. Output is a low-level voltage signal, posing no high-voltage risk if the secondary is open. | Hazardous. Leaving the secondary circuit open while current is flowing can generate extremely high, lethal voltages. |

| Physical Form | Flexible and lightweight (e.g., half a pound for a 5,000A unit). | Rigid, heavy, and bulky (e.g., up to 65 pounds for a comparable range). |

| Installation | Easy. Flexible, clip-around design simplifies installation on busbars or irregular conductors, especially in tight spaces. | Difficult. Rigid design often requires a full power shutdown and custom fabrication for large or irregular conductors [3]. |

| Complexity/Cost | More complex to use due to the required external or integrated integrator. Can be more expensive than basic CTs. | Simpler to use (direct current output). Generally less expensive for standard applications. |

III. Application Scenarios

The choice between an RC and a CT depends heavily on the specific requirements of the application.

| Technology | Ideal Applications | Less Suitable Applications |

| Rogowski Coil | – High-Current monitoring (e.g., up to 5,000A and beyond). | – DC current measurement (RCs only measure AC/rate of change). |

| – High-Frequency and Transient analysis (e.g., power electronics, motor inrush, fault currents). | – Applications where the cost/complexity of the integrator is prohibitive. |

| – Retrofitting or installations with irregular conductors or limited space. | – Standard utility metering where high-accuracy, low-frequency measurement is the sole requirement. |

| Current Transformer | – Standard Utility Metering and revenue applications (high accuracy at 50/60 Hz). | – High-current measurement where saturation is a risk. |

| – Relay Protection and industrial monitoring at power-line frequencies. | – High-frequency or transient current analysis. |

| – Applications where simplicity and low cost are prioritized. | – Installations with irregular busbars or tight space constraints. |

Conclusion

Rogowski coils and Current Transformers are complementary technologies. The Current Transformer remains the workhorse for traditional, high-accuracy, steady-state power monitoring and protection at power-line frequencies. The Rogowski Coil, with its coreless design, offers a modern, flexible, and safer solution that excels in demanding environments involving high currents, wide dynamic ranges, and high-frequency transients, particularly in power quality analysis and power electronics testing.

Copyright © 2024 PowerUC Electronics Co.